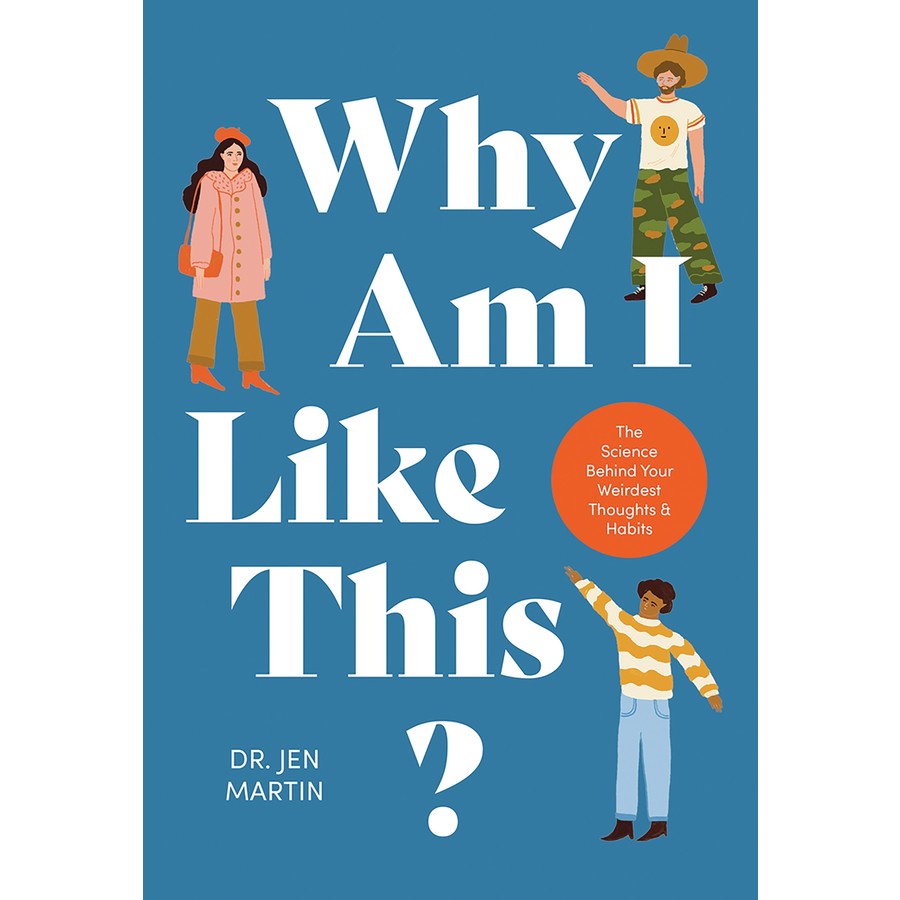

WONDERFUL NEWS: My new book, Why am I like this? is out now! Check it out to learn the science behind your weirdest thoughts and habits.

Hi, I’m Associate Professor Jen Martin.

Leader, Science Communication Teaching Program

Faculty of Science

University of Melbourne

Radio broadcaster

102.7 FM Triple R community radio

Podcaster

Let’s Talk Scicomm

Author

Why am I like this? The science behind your weirdest thoughts and habits (Hardie Grant, 2024)

As a scientist, I spent the first decade of my career chasing possums at night to learn about their sex lives.

Then I decided the most useful thing I could do as a scientist was to teach other scientists to be better communicators. So I founded the science communication program at the University of Melbourne. I love teaching science students how to write and talk about science so that everyone else can understand them. I’ve also been talking about science on Triple R community radio for more than 15 years.